Español: https://solidarityapothecary.org/la-herbolaria-de-lxs-presxs-ediciones-en-espanol/

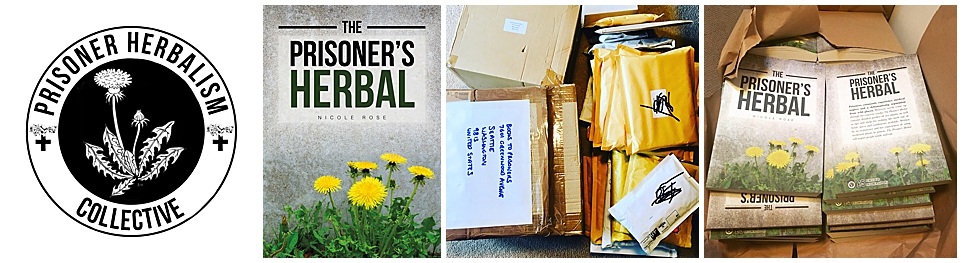

The Prisoner’s Herbal book is written for people in prison who want to learn about the medicinal properties of plants commonly found in prison courtyards. It contains ten detailed plant profiles, as well as instructions on how to prepare plant medicines in prison and more. It is based on the author’s experience of using herbs through her 3.5 year prison sentence.

Two compañerxs have translated the book into Spanish – Jorge and Heather Anne. We have created two editions – one for people imprisoned in the Spanish state, and the other for people incarcerated across Abya Yala, the name in Guna for the so-called Americas, used by millions of Indigenous peoples across these continents.

About the book

Prisoners all over the world commonly experience medical neglect and a dehumanising separation from wild places. However, weeds come up through the concrete cracks. This book contains detailed profiles of ten plants that are commonly found in prison yards with suggestions on how to prepare medicines in prison with limited resources.

It also includes tips and tricks for making the most out of foods, spices and condiments available from the prison canteen (commissary), as well as sections on how to connect with plant allies emotionally and how to care for wounds in a prison environment.

For readers on the outside, it provides practical advice about how to work with common weeds in simple and direct ways and will inspire solidarity across the walls.

More than 3000 copies of the English version of the book have been distributed to prisoners across England, Wales and Scotland and the so-called United States. Making this work happen is the Prisoners Herbalism Collective, a grassroots group of people who love plants and hate prisons.

Why does this book matter?

Prisons in Mexico

Despite the publication of an amnesty that, in theory, sought to reduce the high levels of saturation in Mexico’s prison system, the reality is that the number of people deprived of their freedom has not decreased. On the contrary, it has gone up. This is due, among other factors, to the use of pretrial detention, which keeps a large number of people in prison without a sentence and awaiting trial.

In addition, there is a marked class bias within the prison population, since a high percentage of the incarcerated population is incarcerated for petty theft crimes, motivated mainly by poverty and social marginalization.

Besides the overcrowding, organized crime groups operate within the prisons. In many cases, they work with the open complicity of the authorities, allowing them to carry out their activities and maintain control within the prisons. Violence is a daily occurrence inside the prisons. Inmates must pay quotas, either to guards or to other prisoners, to obtain better food, access to services and even security.

It is worth special mention that the prison complex in Mexico is a racist institution. Thousands of indigenous people spend their days in prison without even knowing what they are accused of, as they do not speak Spanish and have never received assistance according to their culture or language.

There are different types of prisons, with the so-called maximum security prisons having the strictest conditions of isolation and deprivation. They are reserved for high-profile prisoners such as drug traffickers, although they have also been used to lock up political prisoners.

ICE Detention

Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) was created in 2003 as part of the U.S. government’s response to 9/11 that included mass surveillance, racial profiling, and militarism. It is the beating heart of the border regime. In 2020, an average of 20,000 people were detained every day in 200 immigrant prisons and jails across the so-called United States, while more than 185,884 people were deported.

Detention centres are cruel by design—denying liberty, discouraging people from fighting to stay, deterring people from migrating and returning—in order to enable not only widespread detention, but also mass exclusion and deportation. ICE’s horrific detention practices include family separation; sexual abuse of children; unnecessary hysterectomies; use of force; deployment of chemical agents such as pepper spray; arbitrary and punitive use of solitary confinement; prolonged detention; and medical neglect, occasionally resulting in death.

Prisons in the Spanish State

Like all countries, prison conditions are dire. Around 46.000 people are behind bars and 62 people took their lives in 2020. Isolation, physical force, and mechanical confinement are all used profusely. Torture, in its different forms, is a common practice, and this cases don’t get investigated . Racist migrant detention centres run on degrading and inhumane treatment and there is ever-increasing violence and overcrowding. Prisoner labour is exploited to maintain the prison system and to make money for private companies. Dispersement policies of the State separate families – people travel nearly a thousand kilometres to spend 45 minutes to one hour speaking to their loved one through plastic glass.

How to request & order copies

Spanish State

- Request free copies for prisoners by contacting ma************@********il.com

- Buy the book from: https://www.viruseditorial.net/es/distribuidora-comercial/fondo/9396/la-herbolaria-de-lxs-presxs

Mexico

- Request free copies for prisoners by contacting: la*********************@***il.com

- Buy books from: la*********************@***il.com

United States

- Pre-order (ends 21st October) – https://solidarityapothecary.org/product/laherbolariadelxspresxs/

- Request free copies for prisoners by contacting: la*********************@***il.com

- Buy books from: la*********************@***il.com

- You can also use this form, please indicate the language of the book: https://solidarityapothecary.org/prisonersherbalrequest/

How to support the Project

Donate: https://solidarityapothecary.org/support/

Get involved in distributing the books to prisoners. Please contact:

- Spanish State – ma************@********il.com

- Mexico – la*********************@***il.com

- United States – pr*************************@********il.com

Help promote the book! Please invite people to speak, share the project on podcasts, bookfairs and events.

The Second Edition

Where to send entries:

- Spanish State – Virus Editorial, C/ Junta de Comerç, 18 baixos 08001 Barcelona con el título “Segunda edición de la herbolaria de lxs presxs”

- Mexico – la*********************@***il.com

- United States – Prisoner Herbalism Collective, PO Box 220340, Brooklyn, NY 11222