Please note these plant profiles are a work in progress. I will always be adding to them as I keep learning about the amazing world of plant medicine.

Botanical Overview

Latin name: Achillea millefolium

Plant family: Asteraceae

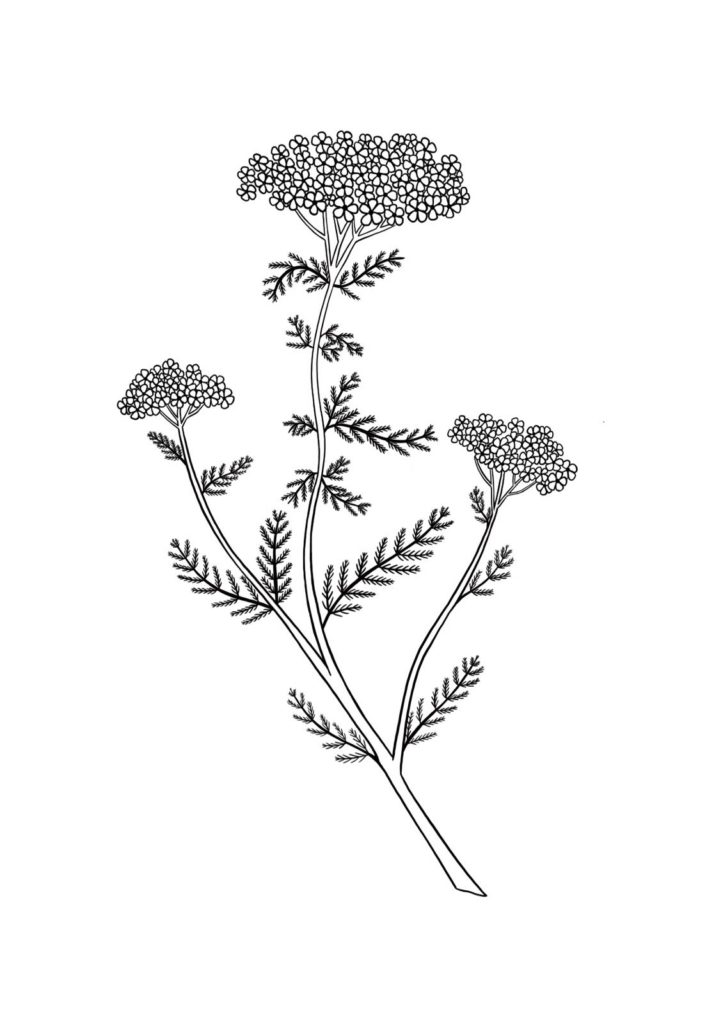

Identification: A short herb no greater than 40cm tall with narrow, darkish-green leaves deeply and intricately cut into short, very thin lobes, the main lobes divided further into smaller ones (2-pinnate) which themselves can be divided (3-pinnate) or toothed. The short, closely-spaced lobes mean that the leaf as a whole is narrower and with a clearer outline. Stems quite stiff, with dense, branched heads of small white or pale pink flowers in summer or autumn. (1)

Other species: There is a vague similarity with Wild Carrot (Daucus carrot) when foraging, however, yarrow is very distinct.

Folk names in English: Soldier’s Woundwort, Herbe militaris, Bloodwort, Sanguinary, Staunchweed, Devil’s nettle, Devil’s plaything, Old man’s pepper, Nosebleed, Carpenter’s weed, Life medicine, Milfoil, Allheal, Squirrel’s tail, Nosebleed, Badman’s plaything, Knights Milfoil, Seven-year’s love, Yarroway, Englishman’s quinine, Carpenter’s grass, Thousandleaf, Noble yarrow, Thousand seal, Dog daisy, Field Hop, Little feather, Warrior plant.

Millefoilum in Latin means a thousand leaves. Achillea comes from the story of Achilles who used the herb to staunch the blood of soldiers wounded in battle.

Chemical constituents: 5% essential oil including alpha and beta pinenes, borneol, bornyl acetate, borneone, caryophyllene, 1,8- cineole, eugenol, farnesene, linalool, myrcene, sabinene, salicylic acid, isovalerianic acid, terpineol, sesquiterpene lactones, chamazulene, thujone; Flavonoids (apigenin, luteolin, quercetin, and their glycosides, artemetin, casticin, rutin and others; Tannins; Bitter glyco-alkaloid achillein/betonicine, stachydrine, achiceine, moschatine, trigonelline etc.; Miscellaneous acetylenes, aldehydes, cycitols, plant acids , resins, achillic acid, asparagines, choline, polyacetylenes; coumarins, triterpenes, cyanogenic glycosides (6)

Food and nutrition

Yarrow has been used to brew beer, as tobacco and in salads and soups. Forager Pamela Michael also includes it in white sauce and suggests eating it as a vegetable with garlic and oil (4). Herbalist Mark Pedersen’s nutritional profile of yarrow shows it is very high in chromium and tin, and high in ash, fat, potassium, riboflavin, selenium, thiamine and vitamin C (2).

Ecological role

Yarrow can be found on dry to moist, neutral, basic or mildly acidic soils in unimproved or semi-improved grasslands in lowlands and uplands. Also on sand dunes and disturbed ground (1). It’s fantastic for insects, attracting bees, wasps, moths, butterflies, flies and beetles. Medicinal Herb Farmers, Jeff and Melanie Carpenter, write that growers can take advantage of yarrow’s incredible insectary power by planting it in proximity to other plants that are prone to damage from herbivorous insects or diseases they carry with them (7).

Cultivation: The Carpenter’s plant yarrow at 12-inch space in rows fourteen inches apart with three rows in a bed (7). Yarrow will soon create a dense carpet over the soil. They are generally harvested in the early stages of flowering with a field knife.

Energetics

- Temperature: Cooling

- Moisture: Dry

- Tissue State: Hot/Excitation, Damp/Stagnation, Damp/Relaxation

- Taste: Bitter, Pungent, Astringent

Health challenges supported by Yarrow:

Herbal actions: Diaphoretic; Antipyretic; Hypotensive/ amphoteric for blood pressure; Astringent; Diuretic; Antiseptic (especially for urinary system); Haemostatic; Spasmolytic; Anti-haemorrhagic; Styptic; Antispasmodic; Anti-inflammatory; Emmenagogue (6).

Bleeding, Wound Care and First aid: Yarrow is potentially the most famous wound herb due to its styptic action of stopping bleeding (internally and externally) from small cuts to internal bleeding and haemorrhage. One of yarrow’s folk names is nosebleed because its traditionally been used during nosebleeds, where people simply roll up some fresh leaves and stuff up their noses! You can also simply chew up fresh leaves and apply to a wound. Yarrow is powerful for all stages of the wound healing process, from homeostasis (stopping bleeding) to promoting inflammation whereby blood and necessary immunity actors move to that area to proliferation and granulation (where new tissue starts to form). Finally, there is the remodelling stage where yarrow is also powerful.

If you don’t have any fresh yarrow you can use dried yarrow that is rehydrated with water (don’t use powders directly on a wound!). For example, you can make it into a poultice or soak a cloth in a tea. It is also great to wash a wound with yarrow tea. Herbalist Sajah Popham describes “So making a tea of yarrow leaf and/or flower (strained) can be great to soak and soften a wound aiding in clearing out debris, disinfecting it, reducing excess inflammation (and pain) and help with the regeneration of new cellular growth” (10). Herbalist and prepper Cat Ellis includes yarrow in her internal bleeding tincture combined with shepherd’s purse and nettles. She also adds yarrow to her wound care tincture with echinacea, spilanthes and berberine, as well as in an antibacterial wound powder combined with marshmallow root, usnea and kaolin clay (5).

Bleeding gums: Yarrow tea swished around in your mouth will have an antimicrobial action, it will stop the bleeding right away and prevent infection. Michael Moore also says that chewing the fresh root or applying the tincture topically after a tooth extraction really helps.

Colds, Flu and Fevers: For years, I would intuitively combine yarrow, elderflower and mint every time I was developing a cold. I was then nicely surprised as I found it referenced as a combination with a long traditional use! I usually just add the dried herbs together with hot water to steep and then strain. Yarrow is a diaphoretic and helps the body to sweat and do what it needs to do to fight an infection (rather than suppressing it). Sajah says “Yarrow is a critical remedy for colds and fevers, especially when someone feels nauseous and experiences period fever,” further adding, “I think yarrow is one of the most dynamic remedies for treatment of acute infection with a broad range of application (respiratory, urinary, digestive, blood, circulatory, fever, topical etc).”

Fungal and microbial infections: Sajah writes that yarrow is full of aromatic volatile oils that display antimicrobial and antifungal actions both topically and internally. This is in combination with its diaphoretic property makes it useful in a wide variety of pathogenic infections both systematically and local, especially for infected wounds in combination with its vulnerary property.

Menstruation: Yarrow is an emmenagogue which means it will promote the movement of menses, it does this by simultaneously stimulating the circulation of the blood as well as draining sluggish fluids down and out through its bitterness. Amazingly, yarrow can also be used not just to promote menstruation, but to reduce it, acting intelligently to support the body. Julie and Mathew Seal write, “the special ability to both stop bleeding and break up stagnant blood makes yarrow a valuable menstrual remedy. It will correct both heavy and suppressed periods and will normalise blood flow if there is clotting.” (3) It is used to treat abnormally heavy bleeding as well as vaginal leucorrhea (whitish or yellowish discharge).

Amani Omejer’s beautiful illustration of Yarrow for the upcoming Prisoner’s Herbal book

Digestive system: Sajah states how yarrow has an affinity for the liver, spleen, stomach and works especially for hepatic portal vein congestion of the body. This is predominantly through both its bitter and carminative properties. Yarrow promotes secretions, alleviating and dispersing tension held in the gut moving out stagnation, cooling heat and stimulating digestion. He also adds, “Yarrow will be helpful when someone has had chronic relaxation of the bowels, like diarrhoea, as the tissues don’t have enough tonal quality to hold in fluids and the stool. Drinking Yarrow tea can be useful for conditions such as leaky gut syndrome, symbiosis, irritation of the intestines, and bacterial infections as Yarrow’s virtues all work to improve the integrity of the tissues.” Yarrow is also anti-microbial against Shigella.

Joint inflammation: Yarrow is not only powerful for inflammation in wounds but also longer-term conditions. Michael Moore describes how yarrow can be used for joint inflammations caused by rheumatoid arthritis and other low-level autoimmune or allergic conditions that settle in the joints.

Urinary infections: Yarrow is useful for urinary tract infections (UTIs) that cause painful, burning urination. It can kill bacteria while simultaneously toning tissues. It also has the diaphoretic properties that help the body respond to all manner of infections. Herbalist Stephen Harrod Buhner’s book includes research that shows how the compounds in yarrow have proven effective against a number of organisms that are associated with UTIs including Candida albicans, Escherichia Coli and Streptococcus faecalis. Yarrow is also useful for people experiencing urinary difficulties from a swollen prostate.

For circulatory conditions: Yarrow has an incredible affinity for the blood and can be used to treat conditions such as varicose veins, hypotension, hypertension and thrombosis. Sajah describes yarrow’s actions on the blood: “Yarrow is used effectively to tone the blood vessels in the peripheral capillaries and veins. Paradoxically, it not only tones and astringes but also acts as a vasodilator, opening up the vessels and allows for more blood to move through the system, thus bringing more nutrients and oxygen to areas that may be lacking.”

Haemorrhoids: Yarrow has a traditional use for haemorrhoids due to its astringency. Sajah says the astringency from the tannins makes it excellent both internally and externally, as it will tighten up the tissue, stop the bleeding, reduce inflammation and pain, and shrink the haemorrhoid itself. It can be added to a sitz bath and also be used internally.

If all these incredible medicinal uses aren’t enough, yarrow is also known in folk medicine as a tool for love divination. Nigel G. Pearson writes how if yarrow would be wrapped in a flannel sachet and placed under a pillow at night then that person will dream of their future lover that night. Yarrow was also hung over newborn babies as a form of protection magic (8). Elisabeth Brooke describes it as a herb for those fighting injustice, with yarrow as protective battle armour (9).

Cautions: Yarrow is not recommended for people who are pregnant because of its emmenagogue action. Yarrow can cause skin reactions in some people and in large doses can cause headaches. It can also decrease drug absorption because of its ability to increase gut motility.

Yarrow and the Solidarity Apothecary

Yarrow will be featured in my upcoming book, The Prisoner’s Herbal. It’s such a powerful ally for folks doing frontline organising work who can more often than not feel like they are at war, and can be physically and emotionally wounded in battle. The chronic stress of grassroots resistance effects everyone in a different way, for people who menstruate, it can really develop into heavy and overwhelming periods, for which yarrow can be a great support.

Sources

1. Plants and Habitats, Ben Averis

2. Nutritional Herbology, Mark Pedersen

3. Hedgerow Medicine, Julie Bruton-Seal and Mathew Seal

4. Edible Wild Plants and Herbs: A Compendium of Recipes and Remedies, Pamela Michael

5. Prepper’s Natural Medicine: Life-Saving Herbs, Essential Oils and Natural Remedies for When There is No Doctor

Book, Cat Ellis

6. Yarrow monograph, The Plant Medicine School

7. The Organic Medicinal Herb Farmer, Jeff and Melanie Carpenter

8. WortCunning – A Folk Medicine Herbal & A Folk Magic Herbal, Nigel G. Pearson

9. Traditional Western Herbal Medicine: As Above So Below, Elisabeth Brooke

10. Yarrow monograph, Materia Medica Monthly produced by the Sajah Popham at the School of Evolutionary Herbalism